The days of easy money and low inflation are over.

Key takeaways

The middle market faces a new era of rising interest rates and higher costs.

Investments that improve productivity are more important than ever.

The end of hyper-globalization heralds the end of an era of low inflation and low interest rates.

Regime changes in global trade, growth and liquidity, along with a significant increase in geopolitical tensions, are reintroducing political and economic risk.

To manage this risk, middle market firms will need to invest within friendlier trading blocs if they are to realize greater yields down the road.

Middle market insight

Global trade is increasingly divided into two blocs, one led by the United States and its trading partners and the other by China.

But it won’t be easy. The cost of capital is rising, and reconfiguring supply chains is difficult and time-consuming.

In the past three years alone, the pandemic, Russia’s war in Ukraine, China’s renewed aggression toward Taiwan and rising authoritarianism have disrupted global supply chains.

Now, global trade is increasingly divided into two blocs, one led by the United States and its trading partners and the other by China.

One bloc maintains state capitalism and industrial policy where the government picks winners. The other adheres to democracy and the rule of law, with pricing and choice determined by market forces.

Amid these tensions, monetary policy has been shocked out of gradualism and dramatically increased the cost of capital.

Wartime shortages and misallocation of resources are threatening growth. If the past 30 years were characterized by insufficient aggregate demand and excess supply, the new era will be shaped by persistent supply shocks and geopolitical tensions.

Middle market insight

One result of rising risk has been the bursting of speculative market bubbles that flourished during the days of easy money.

Other, more benign factors will continue to affect firms’ ability to raise capital. Examples include the impact of Brexit, the cutoff of Russian energy supplies, the fight in the United States over raising the debt ceiling, and the potential end of Japan’s yield-curve control.

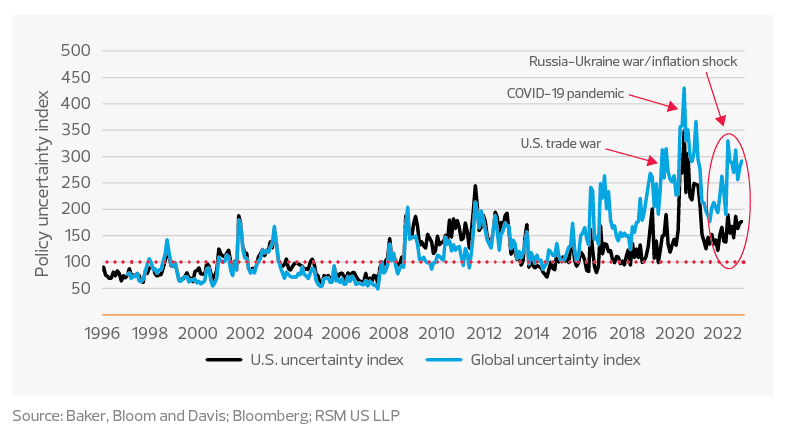

These factors have only added to the policy uncertainty that plagues the world markets.

U.S. and world economic policy uncertainty indexes graph

U.S. financial market risk

The U.S. financial markets have been left balancing high inflation with tighter monetary policy. It’s a lose-lose situation that raises the cost of capital and adds to investors’ perceptions of risk.

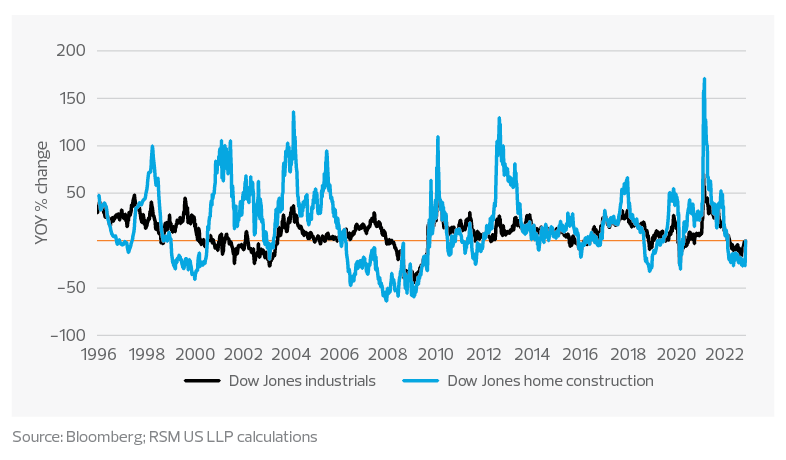

One result of this new environment has been the bursting of speculative market bubbles that flourished during the days of easy money.

Two examples are the excessive funding of fledgling technology firms and the risky investments in the cyber-asset class. Another example is the bubble that formed in select local housing markets during the pandemic.

Plunging equity markets have followed, which are bound to affect spending by individual households and hurt overall growth and future investment.

Yearly returns of the Dow Jones Industrial Average and U.S. Home Construction Index chart

A reassessment of corporate debt

The increase in risk has prompted a reassessment of corporate debt. According to a 2019 study by the International Monetary Fund, the low interest rates in the U.K., the United States, Germany and Japan encouraged businesses to increase their borrowing, often to finance payouts to shareholders rather than investment.

They point out that 40% of that corporate debt—some 15 trillion pounds—would be impossible to service if there were a downturn half as serious as that of a decade ago.

A pandemic later, the rising cost of capital and the risk of a slowdown appear to have taken a toll on the willingness or the ability of corporations to take on additional debt.

Middle market insight

In the past year, surveys conducted by RSM US LLP and by regional Federal Reserve banks show increased investment in productivity among U.S. corporations.

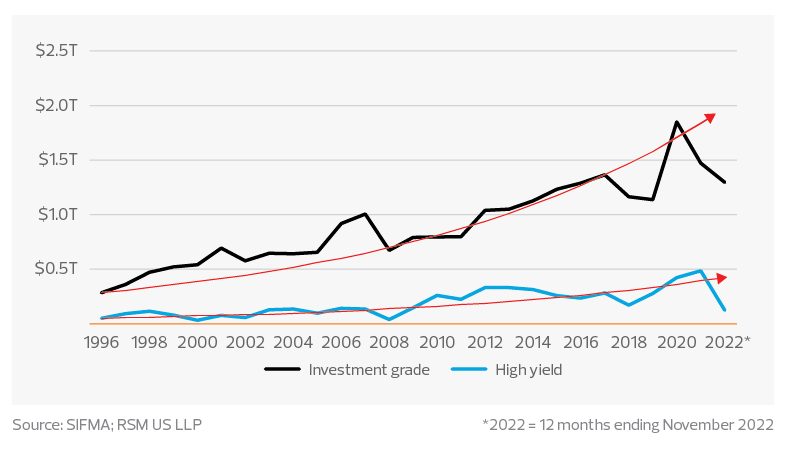

A pandemic later, the rising cost of capital and the risk of a slowdown appear to have taken a toll on the willingness or the ability of corporations to take on additional debt.

The 20% drop in investment-grade (Baa) debt issuance in 2021 was followed by a 12% drop in 2022. After riskier high-yield issuance increased in 2021, it dropped 74% in 2022. Both sectors have fallen below average annual increases experienced from 1996 to 2017, before the trade war and pandemic.

Issuance of corporate debt chart

In the past year, however, surveys conducted by RSM US LLP and by regional Federal Reserve banks show increased investment in productivity among U.S. corporations.

These investments were ostensibly prompted by the pandemic, most likely in response to the shortage of labor, rising labor costs and supply chain problems.

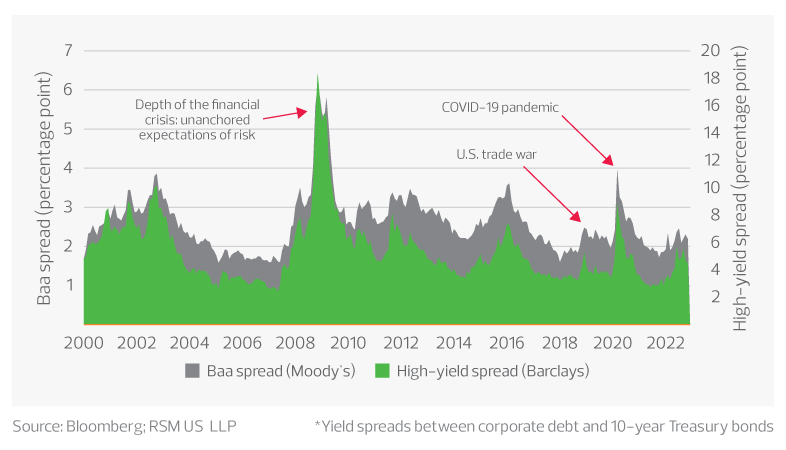

Regardless of the intentions, the corporate bond market is pricing in an increased risk of an economic slowdown. The interest rate spreads between U.S. corporate debt and risk-free 10-year Treasury bonds in 2022 have risen to levels consistent with the economic stress of the trade-war era.

Risk premium of investment-grade and high-yield U.S. corporate debt* graph

Foreign investment risks

Before 2022, we had come to take China’s role as a supplier of goods and its expanding influence around the world as a given. But because of its disastrous COVID-19 policies and a long-simmering financial and housing crisis, a Chinese recession or debt crisis has become increasingly likely.

With China’s restrictive policies in Hong Kong, its renewed belligerence toward Taiwan and its reneging on trade agreements, the schism between Beijing and Washington has only widened.

For example, the Biden administration has shown little appetite for granting China access to U.S. technology or for repealing Trump-era tariffs.

Businesses and investors are looking to shift production to other low-wage centers. Two are Latin America, which offers proximity, and India, whose educated, young, English-speaking labor force is a plus.

If only it were that simple. While India, for example, has a long history as a democracy with a long legal tradition, attracting investment is another matter, Arvind Subramanian and Josh Felman wrote recently in Foreign Affairs.

Investment risks in India remain too high, policy inwardness is too strong and macroeconomic imbalances are too large, the authors wrote.

In addition, firms lack the confidence that authorities will apply the law evenly after an investment is made. By attaching high tariffs to imported parts, New Delhi has provided a powerful disincentive for firms contemplating production facilities in the country.

But Apple’s recent decision to reduce its risk exposure to China may prompt other companies to seek greater investment in places like India, Vietnam and back in the Western Hemisphere.

The takeaway

The reintroduction of greater political and economic risks is going to reallocate investment back inside competing trade blocs. Longer-term returns on investment will require higher short-term costs. That scenario, in turn, will require a different outlook and varied management skills.