A hot U.S. economy will likely cool noticeably in 2019 as the combination of receding fiscal stimulus, higher interest rates and a rising annual operating deficit begin to increase the cost of doing business. We anticipate that a temporary 0.7 percent economic boost from the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) will diminish next year, pushing annualized GDP growth back toward 2 percent before returning to a long-term trend of 1.8 percent in 2020.

Economic activity, employment, wage growth and inflation remain uneven. The mounting urban-rural divide is likely to be exacerbated in coming years as cities closely linked to the new economy (with jobs and skills related to technology, life sciences, finance and trade) see growth, productivity and wages expand at a faster pace than rural areas that remain linked to the traditional economy of manufacturing and agriculture. While many sectors of the economy will experience hot growth in 2019, those that lag behind will have very different policy demands and expectations.

Economic growth in 2018 was largely defined by strong consumption fueled by a historically tight labor market. Next year, the defining economic narratives are likely to be continued trade tensions, more (possibly four) Federal Reserve interest rate hikes, a further decline in the unemployment rate to 3.4 percent and wage growth of 4 percent.

Next year, the defining economic narratives are likely to be continued trade tensions, more Federal Reserve interest rate hikes, a further decline in the unemployment rate to 3.4 perfect and wage growth of 4 percent.

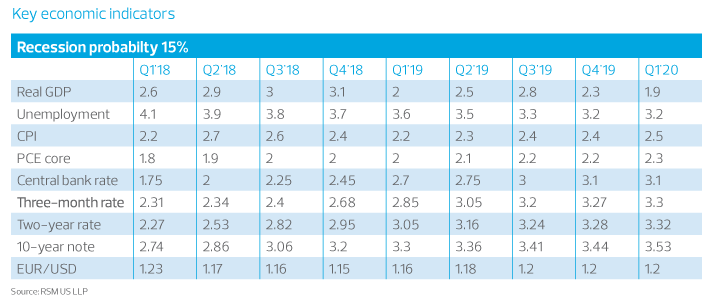

Our 2019 year-ahead forecast calls for a modest growth of 2.2 percent from our 2018 forecast of 3.1 percent. With 2019’s impending deceleration comes the risk of a much more pronounced slowdown in overall economic activity due to the intensification of the U.S.-China trade spat despite a potential 90-day cease-fire agreed upon by the two governments.

Our baseline forecast expects the consumer to be the primary driver of growth in 2019, as government spending eases significantly by midyear. We also anticipate a larger drag from the trade deficit on the back of a stronger dollar amid solid household consumption.

The alternative to our baseline forecast is a faster move back toward priortrend growth of 1.8 percent as the Fed moves into a restrictive policy stance due to rising inflation risks linked to increasing wages and a potential fullblown trade war between the United States and China.

Government spending, which has been the second major driver of growth, will ease in 2019. By the end of the year, about $126 billion in temporary expenditures linked to the TCJA and the 2018 federal budget will expire, weighing on economic activity in the final quarter before spilling over into 2020.

We do not expect a corporate-led boom in capital expenditures to materialize. Rather, the lagged impact of the first phase of the trade spat via import prices diminished capital expenditures in the oil, energy and mining sectors. The expansion of the trade spat with China and possible tariffs on all auto imports will create an unnecessary layer of economic uncertainty during the year ahead that will result in a diminished investment outlook.

It is important to note that an intensification of the trade spat is a policy choice that could be reversed at any time, which would result in upgrading our growth forecast for the year.

Employment

Businesses shouldn’t anticipate any relief on the hiring or wage front next year as the historically tight labor market continues apace. We expect the unemployment rate to fall to 3.4 percent by the end of the year and the economy to generate around 155,000 jobs per month. Supply challenges in the labor market will lead to faster wage growth during the next 12 months, culminating in a 4 percent increase in wages and salaries by the end of the year. Wage growth currently sits at 3.1 percent; however, the three-month annualized pace of growth is now 3.6 percent, and we expect that this late-2018 acceleration will become the primary economic narrative during the first half of 2019.

Financial conditions and interest rates

The Federal Reserve will increase its policy rate by 25 basis points at its Dec. 19 meeting, and likely raise rates four more times next year in increments of 25 basis points. The combination of rising wages, fiscal policy and inflation will lead the central bank to push the federal funds rate toward 3.5 percent by the end of 2019. While that may be neutral terrain for the large multinational firms, in our estimation, it is restrictive for the small- and medium-sized businesses responsible for the lion’s share of job creation and growth during this cycle. Given growing global risks, we would not be surprised to observe a midyear pause in the Fed's normalization policy campaign. In fact, we think it would be in the best interest of middle market companies.

MIDDLE MARKET INSIGHT: Middle market businesses, which often self-finance or participate in the shadow banking industry, should expect a noticeable tightening of financial conditions in 2019 because of central bank policy.

U.S. financial conditions remain 1.3 standard deviations above neutral and are supportive of growth, but have tightened considerably since mid-2018. From a global perspective, financial conditions in Europe are modestly supportive. In Asia, excluding Japan, they are 1.5 standard deviations below neutral, implying a net drag on growth in what had been the most dynamic region of the global economy. This will result in a sustained safe haven move into dollar-denominated assets, which will act to suppress the long end of the yield curve.

We expect the yield on the 10-year rate to end 2018 near 3.5 percent while trading in a range between 3.25 and 3.5 percent next year. If the Fed does not pause its rate hike campaign by midyear, the U.S. yield curve may invert in the second half of 2019. Because the term premium on the 10-year yield is negative, if global risks intensify, we expect a more pronounced safe haven move into dollar-denominated assets, further suppressing yields at the long end of the curve.

Inflation

The gyrations in oil markets that close out 2018 figure to be the major driver of inflation during the first six months of 2019. Inflation will likely ease in top-line estimates that include volatile energy prices, even as it increases for businesses. The U.S. consumer price index currently stands at 2.5 percent, the personal consumption expenditure deflator index at 2 percent and the core personal consumption expenditure (PCE) deflator (the policy variable used by the central bank), all point to general price stability. Even so, it is our contention that the Fed will look right through the easing of prices and continue its rate hike campaign in early 2019.

Over the past year, RSM US Middle Market Business Index participants have noted they have begun to pass prices downstream to customers. Given the risks that U.S. trade policy poses for price inputs, this is setting up as a central theme to monitor in 2019.

Autos and housing

The two most interest rate-sensitive ecosystems are autos and housing. Both have already reached their cyclical peaks. This is of paramount concern to policymakers at the central bank as they look to achieve a soft landing for the U.S. economy as the current business cycle concludes. General Motors said in November it plans to cuts five plants and eliminate 14,000 jobs in the United States and Canada, the result of its move to eliminate slow-selling sedans from its product line.

The U.S. auto sector, despite integrating advanced technology into the fleet, has reached its mature phase. Behavioral changes among the emerging demographic majority and the urbanization of the population are likely to alter the scale and scope of domestic auto production. The updated NAFTA treaty, now known as USMCA, creates incentives for the large automakers to shift new supply chain investment toward the large growth markets in China and India.

![]()

The new rules of origin requirements in USMCA, if approved, along with the evolving wage floor, will result in a bit of sticker shock to domestic auto buyers during the next 12 to 24 months, all of which point toward a much slower pace of auto production in 2019 and 2020. We expect sales to fall back to a pace of 16.5 million annually with risk of a much slower production and sales, especially in the second half of next year.

Meanwhile, new housing investment has remained at 1.25 million annualized units, well below the long-run equilibrium of 1.5 million units. With clear affordability issues mounting due to a lack of inventory, we expect to see one of the softer years in the property market during the current economic expansion. Our interest rate forecast implies a near-term move above 5 percent in the 30-year mortgage rate, which will only exacerbate stresses in the market.

A lack of available units, shortage of available workers with construction skills and an onerous zoning and ordinance framework that adds to building costs will continue to characterize a disappointing residential investment market. We expect residential investment to slow to 1.17 million units in 2019.

Risks to outlook: Domestic and external

The major risks around our economic outlook are linked to trade tensions, a slowing global growth picture, emerging markets, Brexit and the Italian fiscal challenge.

These would negatively affect pricing for middle market businesses across all ecosystems. So far, the Chinese have permitted their currency to depreciate by about 11 percent, thus offsetting the 10 percent U.S. surcharge on exports to the United States. If the United States increases tariffs to 25 percent, there is a risk that the trade spat will turn into a full-blown trade war that would include the use of financial weapons. If that happens, pronounced threats to our growth, employment and inflation forecasts would result.

MIDDLE MARKET INSIGHT: A small hint of a silver lining in the ongoing trade dispute: some middle market businesses are now reporting success in gaining exemptions from the U.S. Trade Representative’s office. (See article: Tariff exemptions for middle market slowly increasing)

Global economic growth should slow to 3.3 percent this year amid a growing series of risks. The level of dollar-denominated debt has increased to $11 trillion from $3 trillion over the past decade. As U.S. interest rates rise, economies with large portfolios of dollar-denominated debt will find it quite difficult to service it. Those economies holding large portfolios of dollar-denominated debt relative to GDP—Turkey, Mexico and South Africa— are the bellwethers for risk around emerging markets.

There are two transmission channels for emerging markets’ economic problems: trade and financial. For example, if there is a move by Turkey to renegotiate its debt or possibly even default, the contagion will spread into the European Union quite quickly via trade, and into financial markets in Spain, Germany, France, Italy and the U.K.

Fiscal policy

In the 2018-2019 fiscal year, which runs from Oct. 1, 2018 to Sep. 30, 2019, the U.S. government is likely to embark on a multiyear period of trillion-dollar annual operating deficits. This fiscal year the deficit is on target to hit $1.3 trillion, at a minimum.

Unfortunately, there is no constituency on either side of the aisle in Washington, D.C. for fiscal probity. As long as global economic risks proliferate, there will be a safe haven move into dollar-denominated assets, which permits the United States to have its cake and eat it too … for at least a while longer. Call it America’s Marie Antoinette moment.

MIDDLE MARKET INSIGHT: Deficits that crowd out investment and cause interest rates to increase are a risk to the vitality of middle market businesses due to their financing and investment needs.

However, moments come and go, and at one point, there will be a positive risk premium placed on the neutral interest rate, which will lead to a much more expensive cost of running large government deficits.

We would recommend putting the fiscal path on a more sustainable pace by attempting to balance the primary U.S. budget (budget excluding interest owed on past debt) during a period of above long-term trend growth. However, with the United States running the most pro-cyclical fiscal policy in recent memory, rather than a narrowing deficit, which would traditionally be seen late in the business cycle, the economy is about to enter a period of multiyear trilliondollar deficits.