Caution by homebuilders in the volatile economy has led to better business fundamentals, but slow production will meet only a portion of society’s need for new homes.

Construction industry outlook key takeaways

Product lead times continue to restrict builders, with three and four times the pre-pandemic rates not out of the ordinary.

The construction industry continues to be hampered by limited availability of skilled labor.

The Great Recession was a once-in-a-generation event that resulted from the global financial crisis of 2007−09, set off by the U.S. housing market crash that sent the construction industry into a downward spiral. It was not apparent then that these events would continue to define the next two business cycles and make a lasting impact on future generations.

Residential and nonresidential construction was slow to rebound coming out of the recession. Developers, homebuilders and construction companies approached each deal with a heightened degree of caution intended to shore up macro-level support.

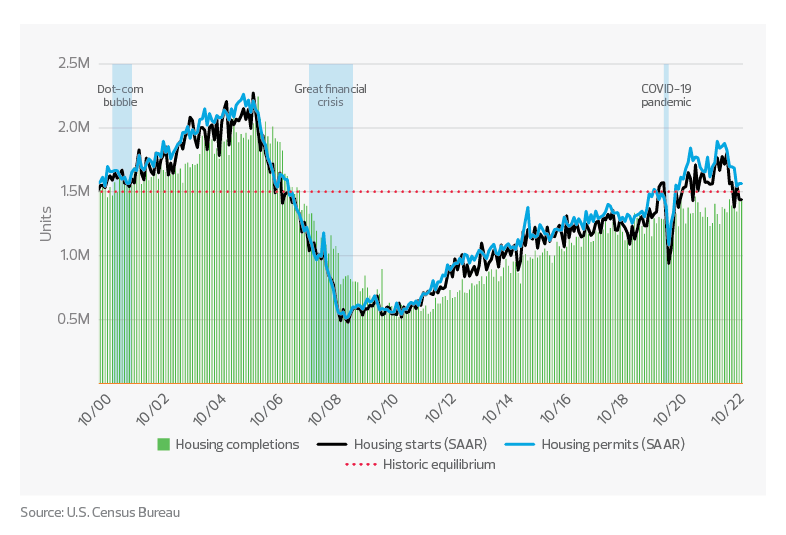

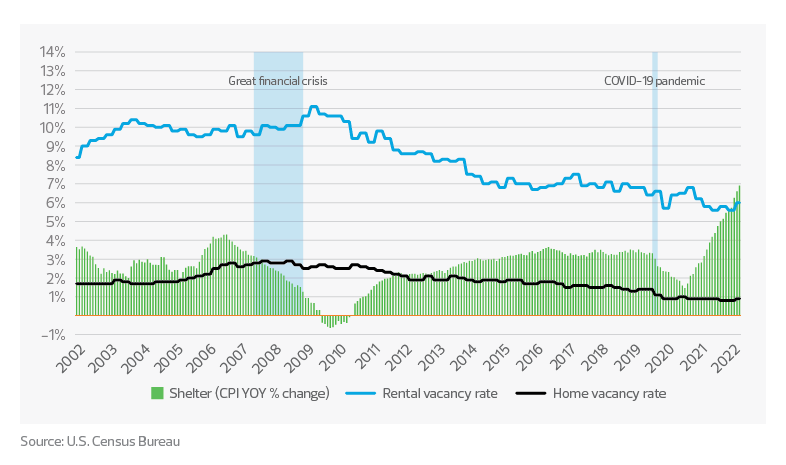

While added caution helped to mitigate risk, it also led to a dearth of new housing, with annual starts and completions sustained at a rate of 1.5 million units. The result was low housing inventory and a decline in rental vacancy rates leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Housing starts, permits and completions

Construction during the pandemic

The pandemic served as the catalyst for significant change in construction. When most of the populace was quarantined in their homes, household net wealth rebounded from recessionary declines—partly due to full recovery of the stock market, federal stimulus funding and reduced spending. At the same time, housing affordability increased, mainly due to the decline in the federal funds rate to 0% in March 2020 to help stimulate the economy. With more money to invest, Americans turned back to the housing market.

Housing sales picked up to levels not seen since prior to the global financial crisis. With the surge in demand, builders pushed to get new homes to market as inventory levels of existing homes hit record lows, driving up prices.

Rental vacancy and median rental rates

The nonresidential building market did not experience a similarly sharp increase in construction services during the pandemic. To be sure, there were sectors that saw rapid growth, such as warehouses and data centers, but they offset more pervasive laggards, including office buildings and hotels.

Like so many industries, construction fell victim to fragile supply chains and a reduced labor force. Building material prices skyrocketed, with the cost of lumber, for instance, at one point rising as much as 264% from pre-pandemic levels.

Additionally, product lead times continued to soar, with three and four times the pre-pandemic rates not out of the ordinary. More recently, distributors of certain electrical transformers have noted lead times of 54 weeks—three times the pre-pandemic levels—and expect them to continue into 2023. Longer lead times have caused project delays and cancellations as inflationary pressures reverberate throughout the economy.

Aside from rising material prices, one of the largest setbacks in the current inflationary environment has been the rapid increase in shelter prices—for both home purchases and rentals—which have risen 6.9% on a year-over-year basis, the fastest annual growth rate since 1990, according to October consumer price index data.

To combat these rising prices, the Federal Reserve has been aggressively raising the federal funds rate, with four hikes in 2022 to date. The concurrent rise in mortgage rates has quashed housing affordability, pushing would-be buyers to the sidelines and often into the rental markets. This has placed short-term upward pressure on rental prices as vacancy rates remain at record lows.

Despite the efforts to combat inflation through the curbing of demand, there is a larger issue facing construction—supply.

TAX TREND: Construction

Construction companies whose projects were stifled in 2020 and 2021 by coronavirus mitigation measures may be eligible to claim employee retention tax credits for the covered periods, subject to eligibility requirements.

For more real estate tax considerations:

The new business cycle

A structural shift is occurring in the broader economy. This new era will be defined by insufficient aggregate supply, negative supply shocks, geopolitical tensions and increased competition for scarce capital.

This shift is already playing out in many facets of the construction industry.

Despite the recent fall in housing demand, there is little evidence to suggest that a rapid influx in housing supply is coming, even with unsold homes in production. The cautious approach taken by homebuilders has led to better business fundamentals, but slow production will meet only a portion of society’s needs, limiting inventory and potentially creating over-leverage.

Additional challenges stemming from permitting and zoning regulations are making it harder and more restrictive to build homes, especially affordable units. Even with laws in place, local regulators are often resistant to building affordable units. A recent state audit in California noted that some wealthy cities were allocated less than their fair share of affordable housing units, with Newport Beach receiving just two units compared to Lake Forest, a nearby, comparably sized town that was allocated 1,100 units.

Much of this is unwelcome news to prospective homebuyers, especially first-time buyers, as limited supply will continue to factor into the unaffordability of housing.

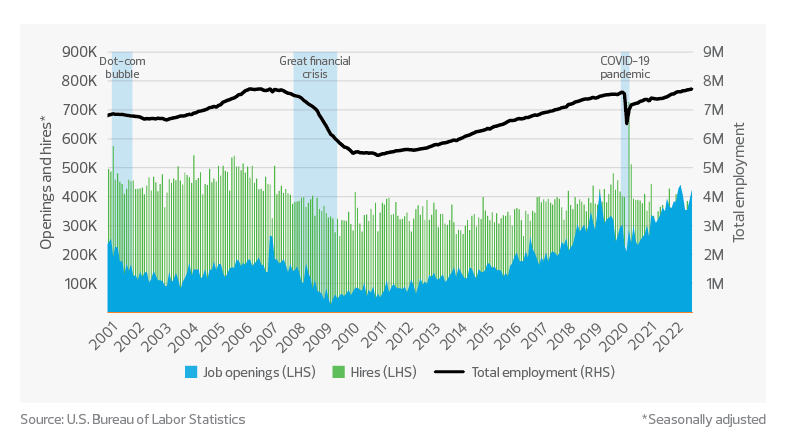

Another challenge facing residential and nonresidential construction is the limited availability of skilled labor. As more and more individuals choose other careers over the trades, the pool of skilled labor has receded. With no faucet to refill the talent pool, many companies may have to pay higher wages to staff for construction services, including to support new projects resulting from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

Construction jobs

The takeaway

The next business cycle will be defined by continued supply shortages. To cope with this growing challenge, construction companies will need to focus their investment of both time and money on identifying, fostering and adopting technological advancement as well as fighting for more effective and efficient regulations over building. If these key areas are not addressed, many of the issues we are facing today will only continue to worsen.

TAX TREND: Construction

As investors and developers reshape commercial office space, they commonly have an opportunity to align environmental objectives with tax benefits through the energy-efficient commercial buildings deduction, or section 179D.

Three types of building systems components qualify for the incentive:

- Interior lighting systems

- Heating, cooling, ventilation and hot-water systems

- The building envelope (insulation, exterior doors and windows and roof, etc.)

These incentives allow for the potential immediate expensing of costs that a company might otherwise capitalize and depreciate over 39 years. The deduction will be indexed for inflation beginning Jan. 1, 2023.